One of the most seminal theological times for me in my early priesthood was the opportunity to do post-graduate studies in Liturgical/Sacramental theology at the famed University of Louvain. Founded in 1425, in the 1960’s due to the linguistic wars taking place in Belgium, the University split with the ancient campus in its historic setting in the town of Leuven where classes were conducted in Flemish and English, and a ‘new’ University built near Leuven in the French speaking section of the country called Louvain la Neuve. I took classes in English in Leuven.

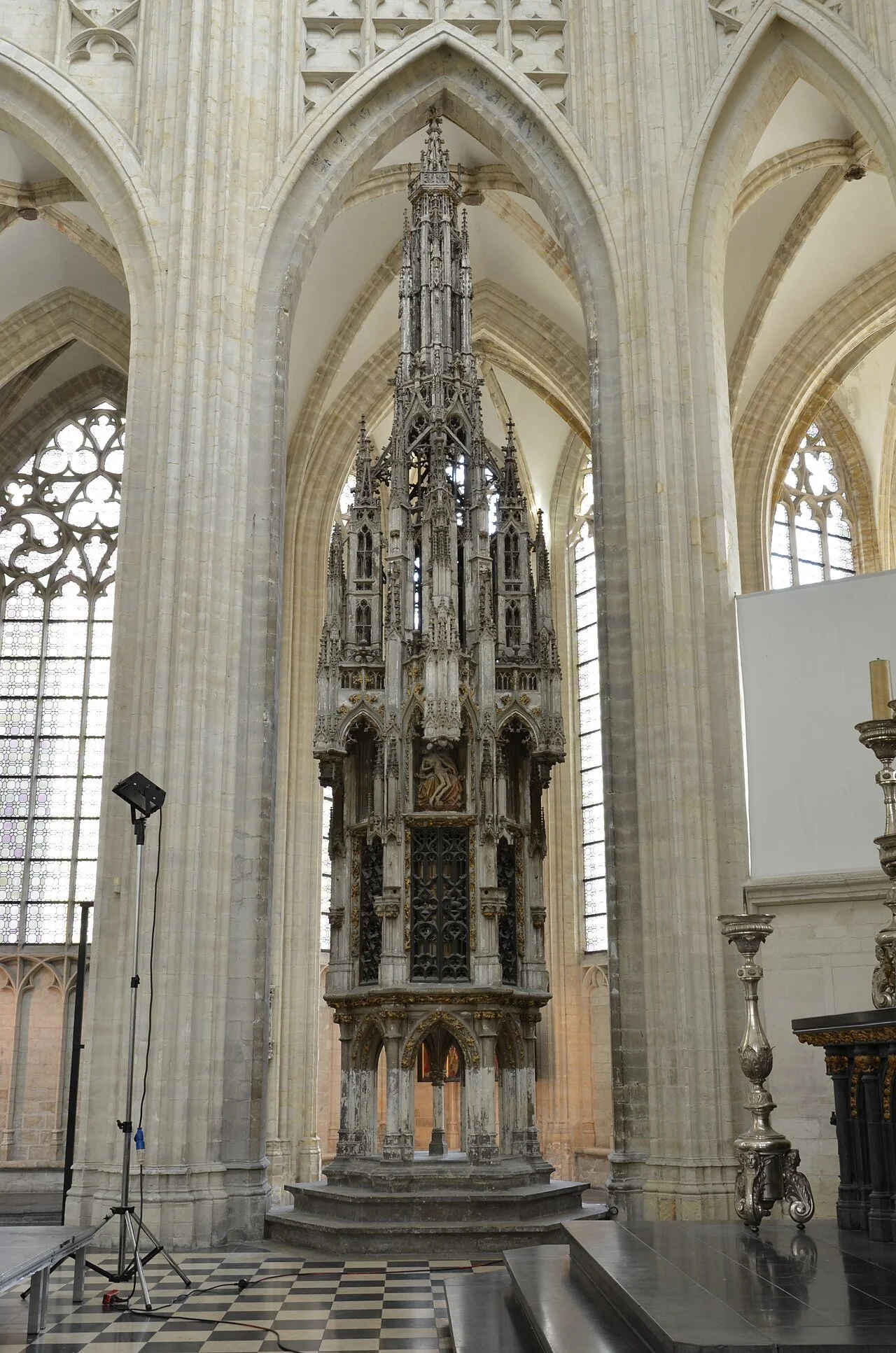

Literally in the center of the old University town stood the collegiate church of St. Peter’s. Built in the 15th century, it was the principal church of the University town. Unique to this beautiful Gothic Church is the Medieval Sacrament Tower where the Blessed Sacrament is reserved. This positioning of the Sacrament, not on the High Altar but near it, reflected the divergent practice that was commonly replaced in the post-Tridentine Church with the Tabernacle affixed to the High Altar. Such a positioning was not always the practice in the Church.

Eucharistic Tower in St. Peter’s Collegiate Church, Leuven, Belgium

Eucharistic Reservation in the Early Church

Scholars of liturgical history tell us that the earliest places for the reservation of the Sacrament were in homes that were often freed from persecution. The primary reason to this day for Eucharistic reservation is that those who cannot be at the Eucharistic celebration due to illness can be taken communion from the reserved Eucharist. I’m sure many of us remember the charming story of St. Tarcisius, a young layperson, taking communion to others during the time of persecution and dying in martyrdom to safeguard the Eucharist.

Alexandre Falguière, Saint Tarcisius

As the Church eventually emerged from being persecuted to receiving status within the state under Constantine and the legitimate practice of Eucharistic adoration ensued in our theology of the Eucharist, Eucharistic reservation varied in this early churches and Basilicas. The emergence of a permanent place on the principal Altar housed in an ornate Tabernacle gradually became the norm.

Baroque Tabernacle in a Church in Germany

An alternative ancient practice was reserving the Eucharistic presence in an ornate and enameled dove suspended over the Altar of Sacrifice.

Eucharistic Dove suspended above the Altar

With the development of a heightened Eucharistic Piety, it was only natural that in time greater prominence would be given to the consecrated element of bread now reserved in elaborate Tabernacles such as can be seen in St. Peter’s Church in Leuven. It was during this time, especially from the 12th century on that the development of Eucharistic processions especially connected with the pious custom of “40 Hours Devotion” developed and continue to this day with a renewed resurgence.

40 Hours devotion at St. John Cantius in Chicago

Sadly, superstitious practices also crept into the piety of the Eucharist at this time, such as gazing at the Eucharist during the Elevation of the elements during mass would suspend time and hence, one would not age!

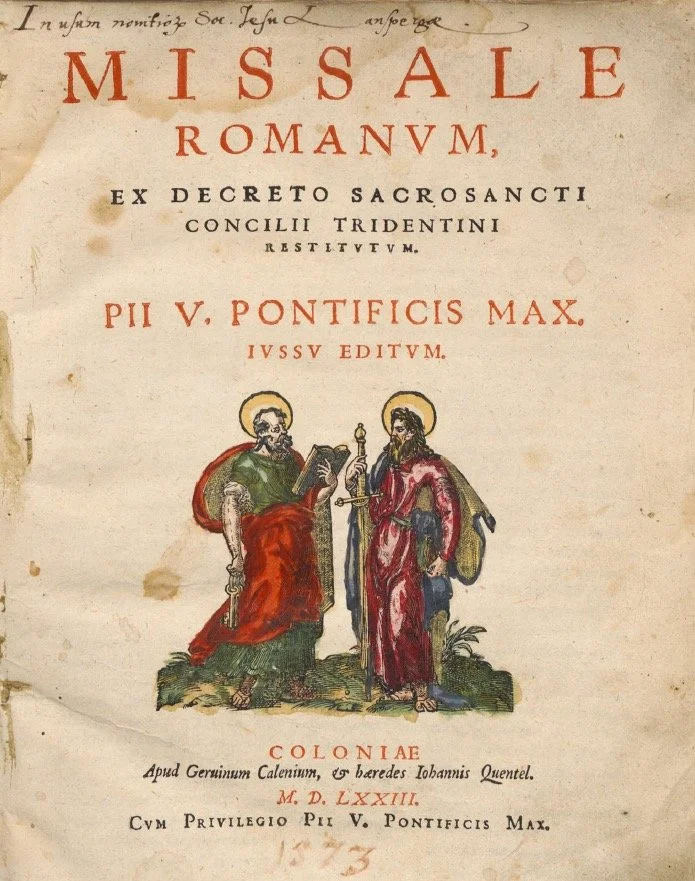

To curb such superstitions, the Council of Trent in her subsequent reform of the Missal that eventually witnessed the Missal of Pius V, brought standardization to the Eucharistic ritual and practice.

First edition of the Missal of Pius V

With the rise of Jansenism that took an overly pessimistic view of human nature, the practice of frequent communion diminished. So much so that the Church was forced to legally require that all Catholics in good standing had to receive the Eucharist at least once a year – the Easter Duty.

It was Pope St. Pius X who encouraged frequent and even daily communion and lowered the age of First Communion to 7 or 8, the age of reason that is the practice today.

To encourage even more frequent communion, Pope St. John XXIII prior to the Second Vatican Council mitigated greatly the Eucharistic Fast, from the old fast from all foods and liquids from midnight until communion to a three hour fast before communion with water never breaking the fast. That was even mitigated by subsequent Popes to a one hour fast from solid food prior to communion.

Eucharistic Presence and Reservation after the Second Vatican Council

The Great Ecumenical Council (1962-1965) called for by Pope St. John XXIII was a Council of renewal and reform in the Church. In keeping with the ancient maxim, ecclesia semper reformanda est (the Church is always in the process of reforming), the Council was one of twenty-one moments in the Church’s history that called for reform and renewal to enable the Gospel of Christ to ring out with greater clarity in the times in which the Church found herself.

The first major issue that the Council dealt with was the reform and renewal of the Sacred Liturgy – the public worship of the Church. This conciliar reform in worship was preceded by nearly one hundred years of scholarship that revealed ancient sources to our common liturgical life. This ressourcement of ancient sources to our liturgical tradition was called The Liturgical Movement. While the Liturgical Movement had a variety of goals, common elements in time emerged:

· A recapturing of worship as a communal experience of all God’s Holy People

· A move toward a vernacular liturgy moving away from celebrations in a language little understood by people today

· A move from a preoccupation with the ‘static’ presence of the Lord in the Eucharistic elements to a renewed appreciation for the ‘dynamic’ presence in the Eucharistic celebration – the Mass.

In December 1963 the Council solemnly promulgated the first of the eventual 16 formal documents, Sacrosanctum Concilium, on the reform and renewal of the Sacred Liturgy. This document received the overwhelming approval of the council fathers with only 4 dissenting votes! (2147 votes in favor, 4 against, 2 invalid votes)

Council Fathers in the Aula of St. Peter’s Basilica during the Second Vatican Council

That document set in motion liturgical and canonical legislation that would eventually witness the first practical fruits of the Council, the most obvious with the gradual introduction of a vernacular liturgy.

The Liturgy Constitution and subsequent legislation also witness changes in church architecture to support a liturgy now reformed and renewed, that is, facilitating communal worship verses a clerical priest-centric liturgy.

The move from an emphasis on the dynamic presence of Christ in the Eucharistic celebration verses the static presence in the Eucharistic elements led to some practical changes in church architecture and sanctuary arrangement. The most obvious and evident change was a move from a fixed altar at the far East end of the nave to a free-standing altar to accommodate Mass facing the people.

Liturgical legislation prohibited a tabernacle affixed to the principal Altar to a separate area of reservation. The separate area of reservation could take three forms:

· Eucharistic reservation in a separate chapel clearly identifiable from the main area of the church.

· A separate area in the church proper that would be clearly visible and properly ornamented away from the sanctuary

· An area behind the altar

Sacrament Chapel in Christ Cathedral

It is important to note that the post-concilar documentation does not give priority to these areas but leaves it up to the Diocesan Bishop and Pastor to determine what would be most fitting in the local setting.

By way of example, when Bishop Tod Brown became Bishop of Orange in 1998 he mandated that all new churches built in the Diocese of Orange have a separate Eucharistic chapel to house the Blessed Sacrament enabling intimate prayer and adoration. If that could not be done in existing churches, the Blessed Sacrament was to be moved to a properly ornamented area to the left or right of the sanctuary. It was not to be in the sanctuary area proper nor behind the principal altar.

Blessed Sacrament Chapel in Mission Basilica San Juan Capistrano

His successor, Bishop Kevin Vann, has approached this delicate area from a different perspective, respecting the decision of the pastor and the pious sensitivities and desires of his parishioners.

Why was the post-conciliar legislation adamant about no longer reserving the Blessed Sacrament on the principal Altar? The language of the liturgy is the language of symbol. Hence, symbols in our liturgy reveal and disclose theological meaning.

The Altar of Sacrifice that symbolizes Christ himself is the privileged place in every church where the Eucharistic celebration takes place. Through this celebration the sacrifice of Calvary is renewed as a lasting memorial and the Lord’s greatest gift to his Church is realized – his real substantial presence, Body and Blood, soul and divinity in the consecrated elements of bread and wine.

It would be symbolically anomalous to enact so great a mystery by the power of the Holy Spirit in every Eucharistic celebration when at the same Sacred Table, the fruit of that celebration is already present in the Tabernacle. The Church in her liturgical legislation wants to clearly delineate the difference between the dynamic Real Presence that comes to us through the Eucharistic celebration that is both meal and sacrifice and the static Real Presence that is the fruit of that celebration and worthy of adoration as well as taken to those unable to be present for the sacred mysteries.